The comparative advantages of competitive and cooperative multiplayer gameplay designs have been studied with mixed results. In this study (paper), we have attempted to minimize other cooperative design attributes in order to focus on evaluating the effects of strong peer accountability on players’ overall and sustained attention levels during competition and cooperation. A novel multiplayer game based on a cognitive task that uses the Stroop effect was developed and deployed in trials where quantitative in-game data measuring players’ error rates and reaction times were collected for comparative analysis. The results show that players demonstrate higher levels of attention when they were made accountable to their partners as they make significantly less errors when cooperating than when competing. In addition, the individual response time data gathered reveals that peer accountability has a more positive influence on the performance of the slower partner and this performance improvement was not sustainable under situation where large performance disparity existed within the team. Physical proximity however, was not observed to have any significant positive influence on players’ performance during cooperative gameplay.

Method

Participants

Participants (\(N=40\)) comprising of undergraduates and graduates were recruited from a large university. Their ages ranged from 20 to 41 years (\(M=26.41\), \(SD=5.34\)). \(55%\) of participants were male and the rest female.

Stimuli

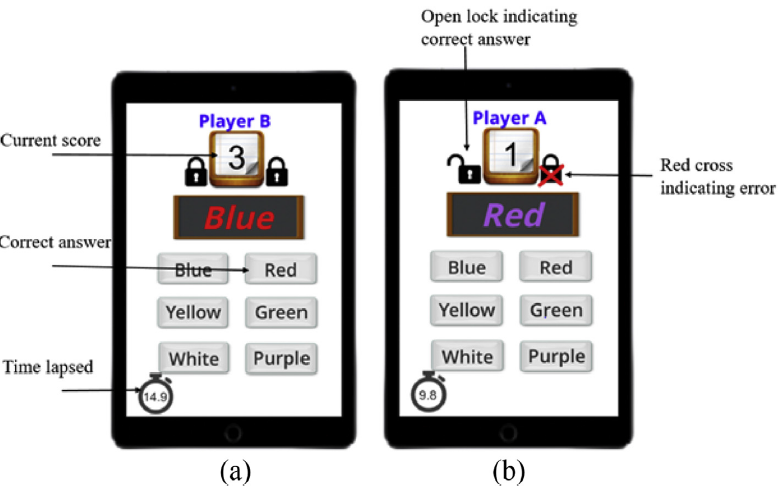

Based on the Stroop effect, a tablet computer-based game was designed focusing on the incongruent condition with unmatched color and word pairs. During the game, the players see a set of words. The colors of the words do not match the words’ meaning, such as shown in Fig. 1(a), the word “Blue” is in red-colored fonts. Players are required to select the matching color of the words. For example in Fig. 1(a), the correct answer is “Red”. The goal of the game is to complete as many questions correctly as possible within the 90 s allocated per round. This multiplayer game is designed with two gameplay modes, namely cooperative and competitive modes. To ensure the two players start the game simultaneously, a third tablet computer (acting as a server) was used by the facilitator to initiate the game when both the players were ready to start.

In competitive gameplay, the goal of each player is to surpass the score achieved by the other. As seen in Fig. 1(a), the current number of correct answers is shown on the top of the screen and the elapsed gameplay time in shown on the bottom left. The two players play independently. After 90s is over, the one who completed the most questions correctly will be announced as the winner with a “Win!” flashed on her tablet, while the other player receives a “Lose”. Both receive a “Win!” in the event of a tie.

In cooperative play, the goal of the game is to beat the score the previous participating team achieved during their corresponding round. The team will be informed whether they have won or lost at the end of each round. Team members cooperate in the following manner. Both will receive the same question simultaneously. As seen in Fig. 1(b), there are two locks on display. Each player controls one lock. More specifically, if one finishes the question correctly, he will see the left lock open with the sound of a delightful chime and if his partner also finishes the question correctly, he will see the right lock open as well. However, if one team member answers the question incorrectly, a red cross will appear on the corresponding lock, as seen in Fig. 1(b), along with the sound of an error buzzer. Only when both players make their selection, can they move on to the next question. If any of the two answers is incorrect, the team gets no points.

Procedure

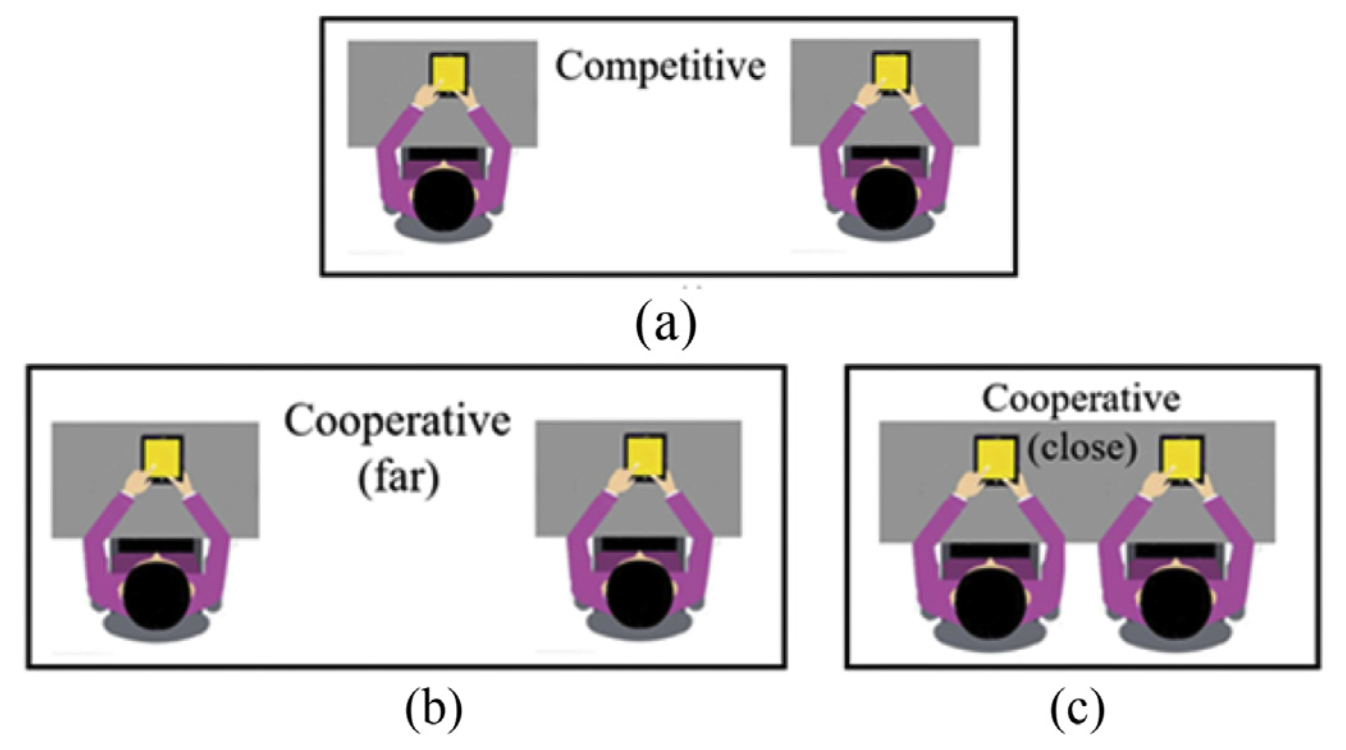

Three modes were investigated in this experiment, as shown in Fig. 2. There was the single competitive mode shown in Fig. 2(a) and the two cooperative modes, both with the same gameplay mechanics except for the physical arrangements of the two part- ners. The first is cooperative mode - apart and the other is cooper- ative mode e close, as shown in Fig. 2(b) and (c) respectively. The 40 participants formed 20 team pairs. Within-subject design was used with the teams playing three different modes in counter-balanced order. On arrival at the laboratory, the participants filled out a consent form and answered some profiling questions before the facilitator started the experiment. Firstly, there was an individual Fig. 2. The three modes: (a) competitive mode, (b) cooperative mode e apart, (c) cooperative mode e close. practice session which allowed the participants to familiarize themselves with the Stroop test task. In this practice session, the participants were required to finish ten questions correctly. After the practice session, the participants were asked if they needed more practice. If not, they started the formal experiment where the participants did three sessions using their assigned order. Each session consisted of two rounds of 90 s duration gameplay. Before the cooperative gameplay session, there was also an additional practice round to help players understand the cooperative game- play design. Participants also answered two different survey questionnaires, one per in-between sessions rest period and in the sequence dependent on their counter-balanced order. They were asked to rate their effort, focus and preference as soon as they were able to compare the competitive-vs-cooperative modes or the apart-vs- close proximity modes. Written feedback and comments were also collected.

Measures

In our study, the reaction time and error rate were both used to measure the attention level. Reaction time is defined as the time lapsed from the question presented to the question being answered. And error rate is defined as the ratio of the number of incorrect answers to the number all the answers completed. Players who do not pay attention to the task is expected to take a longer time to complete the task and is more likely to make mistakes than when they are focused on the task at hand.

Data analysis and results

Competitive mode versus cooperative mode

RQ1. Which multiplayer gameplay mode, competitive or cooperative, results in higher level of attention in a cognitive task?

The differences in error rates between the competitive and cooperative modes are significant, (\(t(39)=2.673\), \(p=0.011\), \(d=0.432\)). Partici- pants made relatively less errors during cooperation (\(M=2.20%\), \(SD=3.40%\)), than during competition (\(M=3.23%\), \(SD=4.35%\)).

Temporal performance changes

RQ2. Is there any difference between the attention levels at the starting and ending stages of the game? And if so, how does it differ in the different gameplay modes (competitive vs. cooperative)? The reaction times increased from the start stage (\(M=1.035\), \(SD=0.186\)) to the end stage (\(M=1.083\), \(SD=0.174\)) in the coop- erative modes (\(t(39)=-3.248\), \(p=0.002\)). In contrast, the change of average reaction times in the competitive mode was not significant (\(t(39)=-1.242\), \(p=0.222\)) from the start to the end. These results suggest that the temporal performance decline occurred only in cooperative mode but not in the competitive mode.

Faster and slower players

RQ3. Will group role (i.e. the faster or slower players) affect attention level in competitive and cooperative modes?

The results show that for faster players, there was no significant difference in error rate between the competitive (\(M=1.98%\), \(SD=1.62%\)) and cooperative gameplay (\(M = 1.61%\), \(SD = 2.17%\)) modes, (\(t(19)=0.951\), \(p=0.354\)). However, the slower players made significantly fewer errors in the cooperative mode (\(M =2.78%\), \(SD=4.28%\)) than in the competitive mode (\(M =4.48%\), \(SD=5.74%\)), (\(t(19) = 2.628\), \(p =0.016\)). These findings imply that cooperation can help the slower players improve their accuracy in the cognitive task and this improvement is not at the expense of the faster players’ performance.

Paired t-test revealed that in the cooperative mode, the temporal degradation of reaction times were significant for both the faster players, and slower players. However, in the competitive mode, there was again no significant decline in reaction time for both the faster players and slower players. These results suggest that the players’ performance in terms of reaction time degraded over time during cooperative gameplay. And this degradation occurred for both the faster and slower players. Fatigue could be a possible explanation if not for the fact that this temporal performance degradation should be equally applicable during competitive gameplay but is not significantly present. Some other factors could be at play here.

Large and small disparity

RQ4. Will performance disparity between partners affect temporal performance during cooperation?

For those groups with large performance disparity, paired t-test suggested significant temporal performance decline occurred from the start stage (\(M=1.006\), \(SD =0.117\)) to the end stage (\(M =1.064\), \(SD =0.136\)), (\(t(15)=-2.505\), \(p =0.024\)). Interestingly, for those groups with small performance disparity, such decline was not significant (\(p=0.140\)). These results imply that the player’s performance seems to degrade with time during cooperation only when there is a large mismatch in ability between partners in solving the given task in a timely fashion.

Summary

This study presented quantitative empirical support for the positive influence of peer accountability on attention levels in a conjunctive cognitive task. Further evidence was also provided to support the Kohler motivation gain and Kohler discrepancy effects by demonstrating that the Kohler effects are equally applicable to cognitive-oriented cooperative tasks as they are to physically-oriented ones. The implication of these findings for game or collaborative application designers is that one can employ a cooperative design with strong peer accountability to increase players’ attention and performance in terms of accuracy. However, to maintain such positive influence of peer accountability, the discrepancy between the members’ performance must be properly moderated.